A Conversation with Curtis Chong.

In July 2024, I had the opportunity to interview Curtis Chong, a dedicated advocate for accessibility and voting rights, alongside Colin Wong from gotomedia, via Zoom. Our conversation focused on the strides made in accessibility across the U.S. and the challenges that remain. Thanks to Curtis’ lobbying and advocacy, he has contributed to the improvement of more accessible mail-in voting practices in the two states where he has lived: New Mexico and Colorado. With the upcoming election on the horizon, the importance of accessible voting is greater than ever. It is crucial that every citizen—regardless of age or ability—has the right to vote privately and independently.

___________________________________________

Kelly:

Hi, Curtis. Very happy to meet you. Can you share a bit about your background?

Curtis:

My name is Curtis Chong, and I’ve been totally blind since birth. I’m officially retired now, but I do consulting when time allows. I have over 40 years of experience with mainstream technology. I was there in the early days of DOS (the Disk Operating System) and Windows, and I was one of the agitators that beat companies like Microsoft and Apple – to make their operating systems usable and accessible to people who are blind. I’ve worked with the section 508 standards twice on committees. A long time ago, I wrote a short paper for the National Federation of the Blind and Computer Science about what blind people would like to see in speech synthesizers and text-to-speech technology when all we had was text-formatted screen terminals. So, I have a long history.

Kelly:

That’s impressive! Tell me how you became involved in making voting more accessible.

Curtis:

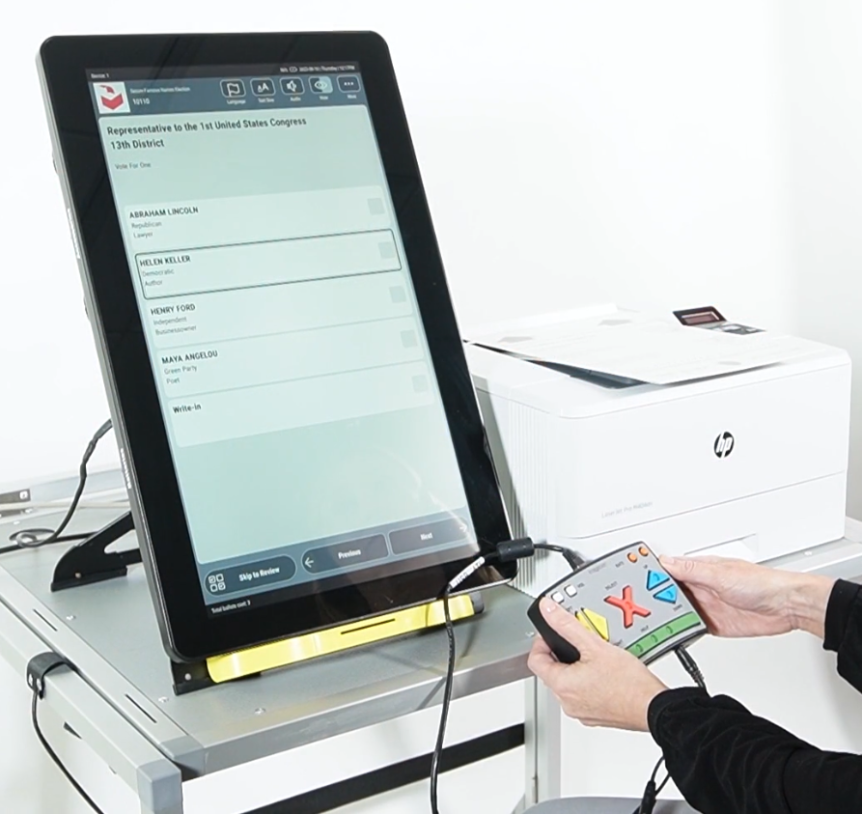

It really began in New Mexico, where I lived for about six years. I learned that the state had a strict, no-excuses absentee ballot, but all the other voting had to be done on-premises at the polls. A year after I moved there, in 2014, New Mexico spent around $6 million to purchase a so-called accessible voting system that would be used at the polls.

The county in Albuquerque, where I was living, was having a mock election day, so my wife and I went into the voting place to try this new equipment, and honestly, I was pretty incensed by how bad it was. The speech synthesis was terrible—words were pieced together with pops and clicks, and when you tried to speed it up, it would chop off words. It was something no modern screen reader would ever do.

Kelly:

So what did you do?

Curtis:

I lobbied very hard with my blind colleagues in the community, and I learned that New Mexico had a printed absentee ballot that you could ask for as a voter without a reason. You could just say, I want to vote absentee, and then they would send you the ballot. Of course, the ballot was in print. My first reaction was that this is not going to work for blind people because we’d always need help marking the print paper, and that’s not acceptable.

Around 2015, 2016, and we got the law changed so that blind voters – legally blind voters, not print disabled — could request an accessible ballot online. What I sold to the legislature was a secure, web-based, accessible ballot. A person could mark that ballot on the computer and then they could print it, sign it, and send it in an envelope specially set up for that purpose.

This wasn’t an original system. Maryland started the whole model, creating a similar system in 2011 or 2012, and gave away the code to other states upon request. So, New Mexico got the code for free, did their own tinkering and stuff with it, and by the 2017 election we had the first accessible absentee system that was only available to the blind.

In 2018, I retired from my job at the Commission for the Blind in New Mexico and moved to Colorado.

Kelly:

Incredible. When you moved to Colorado, did you find similar challenges?

Curtis:

Yes. As a vote-by-mail state, Colorado had a system that was even less accessible than New Mexico. Your ballot gets mailed to you on paper, then you fill it out and mail it back. You can go to the polls if you want, but most counties were using a system similar to New Mexico’s with bad speech and sluggish software. The one and only time I voted at the polls in Colorado, I decided this has to stop.

We were more successful in the Colorado legislature because we started with the first bill, asking for electronic ballot delivery so that we could request the ballot. This first bill made this service available to anybody with a disability, as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act. When I highlighted the fact that they could get the code for nothing, we gained enough support to address a new system. Eventually, money was appropriated to purchase a new system.

You could be in a wheelchair, and you would be okay. You could have a learning disability, and you’d be okay. Anybody could request to have an electronic version of the ballot available to them, but you still had to print it. You still had to sign it. You still had to put it in the mail or a drop box to get the thing in.

We love to vote in Colorado, with multiple elections per year. But many in the blind community told me: “I don’t have a printer. What am I going to do?” So, around 2020 we went to the legislature again and pushed for a way to have ballots sent in electronically. Opposition came from people worrying about fraud, like the League of Women Voters. We compromised and limited the bill to people with a print disability, not just the blind. It’s not just dyslexic. It’s anybody with the inability to work with print, very similar to the print handicap that our National Library Service uses to determine eligibility for its services, with language lifted from the Marrakesh Treaty.

Kelly:

Is it actually called print disability?

Curtis:

It’s actually called ‘People with Print Disabilities.’ It has an articulated definition of the inability to use print. For example, if you can’t physically pick up the ballot and mark it, that person would qualify. This model works better than what some states do because you don’t have to pre-register as someone with a print disability to use the system — you just need to know which website to visit, put your voter information in, go to a very accessible voting web page, vote, review your ballot, and then send it in. There was a wrinkle in Colorado because the state requires a voter’s signature on the ballot envelope. So our law enabled print disability individuals the ability to submit without signature. However, this caused people to be forced to supply an electronic copy of identification. Can you believe this?

Again, there was opposition and emphasis that this system creates a huge security risk. The League of Women Voters actively work to discourage people from using the system. I keep occasionally having dialogues with them.

For some people, this may be a luxury or an I want to have, but for other people … the ability to return your ballot electronically is more of a necessity. It’s not nice-to-have for some people. It is the only way they can vote. When all they want to do is have a ballot they have marked privately and independently. Those are the two concepts that we tie together in all of this.

Kelly:

I was going to ask you about the concept of autonomous or proxy voting—how you can vote privately without assistance. Is there a term for that?

There is no single word for that. So, we use privately and independently together.

Curtis:

There is no single word for that. So, we use privately and independently together. Both are equally important. But there is no one word for that. You must be able to mark your ballot on your own and you must be able to do this without anybody’s help. Period. Because that is the only way you can guarantee your ballot is truly secret, right?

In my conceptualization of the term independent, it doesn’t mean I never get any help to do anything. I tell this to lots of blind people. It means I control the manner in which the help is provided, and the amount of the help I get. Because there are some blind people with other conditions who need other people to do things with them.

I wrote an article a little while ago that got published about how security should not trump independence and the ability to vote privately and secretly. We recognize there may be some security issues, but in the cause of ensuring that the voter has the ability to mark their ballot on their own with no help from anybody, you sometimes have to make some compromises.

Kelly:

You mentioned Tusk Philanthropies earlier. Can you tell me more about the systems they’re working on?

Curtis:

Tusk Philanthropies who have been trying year-after-year to have blind people participate using a mobile phone, like iPhone or Android, to not only mark their ballot but also do end-to-end verification once you’ve delivered it. They’ve done a number of tests I’ve been involved with, including at the 2022 National Federation of the Blind Convention in New Orleans, where we tested and provided feedback, like how VoiceOver works on iPhones. You’re less likely to find a blind person who lives alone or with family using a full-fledged Windows or Mac computer – versus a blind person using a mobile phone. And that is, maybe, the only method they have for going online.

Kelly:

It’s great!

Curtis:

You know, there are complexities involved, which is a two-edged sword. In a sense because if we who are blind have all this great technology that we can use, that’s one positive aspect. But the downside of that is, what do I have to learn as a blind person to be able to maximize the benefit that technology provides to me?

And what I’m learning, as I have talked to people over the years, is as a newly blind person or even as a person like me who’s been blind all my life, but who doesn’t feel comfortable with using technology. Then what I have to learn has become increasingly more complex, and I have to remember more things. Think, for example, and I oversimplify this, if I’m having blind prejudice. I hope I’m not guilty of this, but I tend to think that if you’re a user, a person who uses a mouse, you can see the screen 20/20, you don’t have to memorize 5,000 keyboard commands to do things on the machine. You just look for the icon, you click on it, and things happen.

“If you’re a user, a person who uses a mouse, you can see the screen 20/20, you don’t have to memorize 5,000 keyboard commands to do things on the machine. You just look for the icon, you click on it, and things happen.”

So, the science or the art of designing something powerful to use, but yet easy to learn still eludes most people who are putting products into the market. What’s easy for a visual person may not be what a non-visual person would regard as easy, and I hate to say this because I’m not a fan of the separate but equal principle … I’d rather have our stuff be woven in with everybody else’s, but I also recognize there are some hard realities that are getting in the way, you know?

Kelly:

Can you tell me about companies you think might be ‘getting it right?’

Curtis:

There’s a company called Tusk Philanthropies headquartered right here in Denver. They developed Vote Hub, and the lady’s name is Jocelyn Bukuro. She’s here in Denver. Everybody knows who they are. Everybody knows what they do.

Also, there are a small handful of voting technology companies that have focused most of their energy on developing an accessible Windows interface for the voting process. Companies like Democracy Live have an enhanced voting system called OmniBallot. You can do a mock election. You can participate in the voting, but it is only available for specific approved groups and locations. For example, in Colorado we use the Democracy Live OmniBallot system not only for print disabled, but also for the uniform and overseas voters.

But equally important, you know, it is functional. I could use this system on my iPhone, and I could use this system on a Mac. So I would say, Democracy Live and OmniBallot systems are a good example of something that is already proven to work on multiple platforms.

Democracy Live and OmniBallot systems are a good example of something that is already proven to work on multiple platforms.

Kelly:

How many states have accessible voting now?

Curtis:

The majority of them do not have accessible online voting. Online voting is fraught with perceptions of risk and fraud. And what’s worse, familiarity with technology is an important concept that nobody thinks about in the voting process. If I touch a polling machine that talks to me once every year or every 4-years, I’m going to spend a lot of time going through the ballot because I don’t know what buttons to push to make something happen. Sometimes, I spend 10 minutes just trying to figure out how to get started.

Kelly:

Yes, I understand. There are so many angles here that are interesting.

Kelly:

Curtis, this is great. We really appreciate all the work that you’ve done, especially in Colorado, and we hope to highlight this for other states to emulate. Thank you so much.

Curtis:

You’re so welcome. Have a great afternoon. Thank you very much.

Apps and Systems Related to Accessible Voting

| App/System Name | Description |

| Vote Hub | The National Library Service provides a mobile app for blind and print-disabled users to download audiobooks. |

| Democracy Live | A voting technology company focused on developing accessible systems, including the OmniBallot system. |

| OmniBallot | A system that allows accessible voting and has been used in Colorado for voters with print disabilities. |

| BARD Mobile* | A mobile app provided by the National Library Service for blind and print-disabled users to download audiobooks. |